This Authentix article has been published as a part of World Trademark Review’s Anti-Counterfeiting and Online Brand Enforcement: Global Guide 2024. To learn more, please visit their website.

By Kristi Browne, Authentix

Counterfeiting, smuggling, diversion and infringement – collectively known as illicit trade – are growing global problems for businesses and consumers. With an increasing volume of counterfeit goods being trafficked globally and seeping into supply chains, a well-strategised brand protection programme is more essential than ever to shield what matters most to businesses: customers, brand identity, reputation and revenue.

This growing epidemic of illicit trade extends across a multitude of industries, including food and beverages, pharmaceuticals, health and beauty, apparel and a host of other consumer and commercial products. Its effects translate into financial losses for brand owners and, more importantly, added risks to consumer health and safety. Falsified products manufactured without regard for standards, required ingredients, quality control or government oversight can imperil consumer safety and create a lack of confidence in a trusted brand.

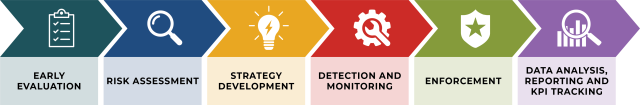

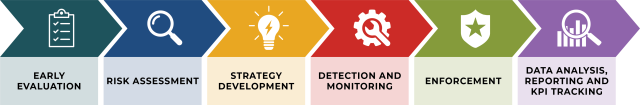

Steps for developing and implementing a brand protection strategy

Creating a brand protection plan for companies means working together across different parts of the company and locations around the world. It also means building relationships with outside groups like Customs, police and government agencies, as well as stores, websites and suppliers.

The following steps are recommended when developing an effective brand protection programme.

1. Early evaluation: Before a company can take advantage of these benefits, it needs to fully understand how serious and widespread the problem of theft can be. The first step is to evaluate the problem. It is also important to evaluate which anti-counterfeiting security methods work best for a company’s product and industry. This will allow the brand owner to get the necessary information on possible security features and packaging design that might be required as part of the final product launch.

2. Risk assessment: When identifying product risk, it is important to develop a risk inventory for the products. The level of risk associated with each product will differ depending upon a multitude of factors, including supply chain complexity, geography in which the product is sold, price points, margins, complexity to copy and total expected demand. The next step is to assess the potential brand damage. With brands being among a company’s most valuable assets, the fragile bond of trust between consumers and products cannot be risked. Any injuries or deaths caused by counterfeits can destroy this relationship. Top management should be aware of this risk and committed to demonstrating leadership on the issue. Brand protection managers and the marketing team should also be involved and participate in assessing the risk of counterfeit attacks and the value of all proposed strategic solutions.

3. Strategy development: At this point, responses to the most pressing threats can be translated into action by organising a method for management, information and technology tools to respond to threats. This is also the time to allocate resources appropriately based on risk areas and to draft a communications plan that covers potential causes of risk, avoidance actions, transference and mitigation actions, and potential impacts and contingency actions.

4. Detection and monitoring: To effectively protect a brand against counterfeiting, businesses must employ comprehensive detection and monitoring strategies that show dedication to enforcing their intellectual property rights and prosecuting violators. This includes implementing a variety of security features on product packaging, conducting educational campaigns for public awareness, enhancing legal penalties for counterfeiting, inserting strict anti-counterfeiting terms in vendor contracts and performing unscheduled audits on distribution partners.

It is also crucial to vigilantly monitor online and physical marketplaces for unauthorised sales, fake profiles and counterfeit listings, and to deploy anti-phishing software. This is essential to detecting threats early and acting swiftly to mitigate brand infringement.

5. Enforcement: Keeping a brand safe means making sure that rules and responsibilities related to intellectual property are properly observed, both online and in the physical world. This task often requires collaborating with the right authorities to handle issues like illicit manufacturing, copyright infringement and counterfeit products being sold, shutting down fake websites, and taking down counterfeit listings.

6. Data analysis, reporting and KPI tracking: Businesses should prioritise thorough reporting and analysis, as well as the tracking of key performance indicators in order to monitor the effectiveness of a brand protection strategy and prevent counterfeit activity as much as possible. This enables them to assess the extent of intellectual property violations and tailor strategies to enhance security measures, moving beyond mere takedown metrics to focus on substantial reduction of infringements. By shifting their perspective on brand protection from a cost to a strategic investment, companies can not only safeguard their assets but also unlock new revenue streams through focused and outcome-oriented actions.

What brand protection solutions are right for my company?

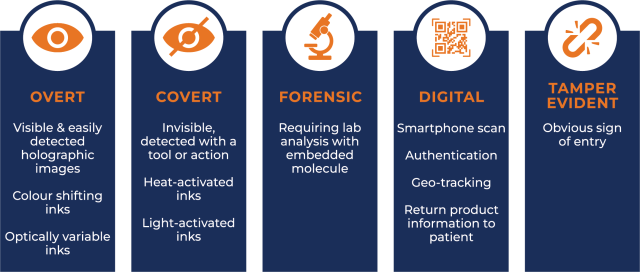

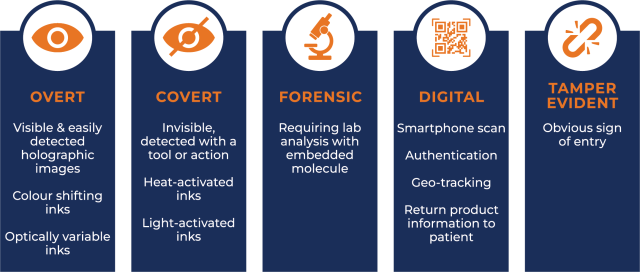

Anti-counterfeiting features may be both overt and covert and can be applied in many ways. These include in-product, on-product in the form of labels and closure seals, on cartons where containers of products are stored, into plastic parts of individual packaging, and even onto metal and glass components of packaging.

Each feature serves a unique purpose. Covert or invisible markings enable trained inspectors to quickly authenticate genuine products in the supply chain, identify the source of diversion, or determine other illicit activities. Overt features allow the end consumer to verify the authenticity of their purchased product. When combined with careful design and production quality controls in authentic product manufacturing, these features raise the bar of complexity for counterfeiters and make the product a less attractive target.

Overt security

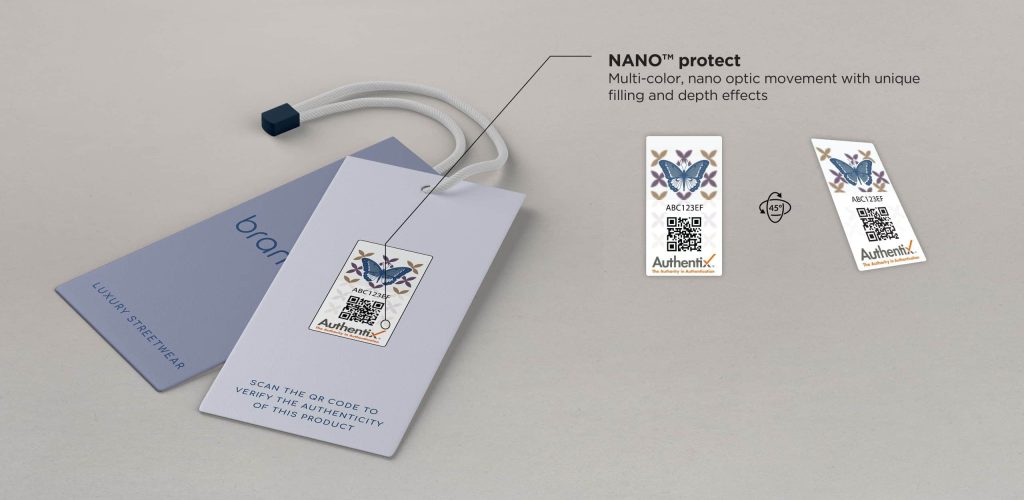

Visible security features are valuable to product authentication. Such measures include holograms, colour-shifting inks and security threads that are visible to the naked eye or felt by touch, and that are difficult to reproduce or copy. Other examples include microtext, thermographic ink and even micro-optics (such as the blue lenticular strip found on the current US $100 bill).

Although visible security features are a starting point, counterfeiters are creative. Even if a visible authentication feature is hard to recreate perfectly, a counterfeiter with the right tools and illegal intent only needs to copy it closely enough to confuse a consumer who just glances at a package. Additional measures create layers of security that make it more difficult, even impossible in some cases, to copy or duplicate security features.

Overt security tactics can include:

• optically variable inks;

• nano-optics with 3D vivid motion, depth and colour;

• colour-shifting foils and inks;

• holographic/pictorial foils;

• pearlescent inks;

• gold and silver inks;

• thermographic ink;

• microtext;

• anti-tampering technologies (tamper-evident closures and labels); and

• optical security technologies (holographic seals and labels).

Covert security

High-security covert features can be embedded into labels, closure seals or other features of product packaging. Although these covert markers are invisible to the naked eye, they can be found and measured with specialised handheld instruments using proprietary optics and detection algorithms for rapid, secure field authentication. Additional forensic layers of security can be embedded into materials and confirmed through more extensive laboratory analysis for evidence to further prosecute profiteers.

Covert security tactics can include

• heat-activated inks;

• light-activated inks;

• fugitive inks;

• inks or materials with specialised fluorescing taggants;

• ultraviolet activated inks; and

• machine-readable electro ink.

Semi-covert security

As the name suggests, these are features that might not be noticed until someone closely examines the product or package.

Forensic security

Forensic analysis involves laboratory testing of products via an embedded component or molecule added to a substrate or solution to determine authenticity. Unique product elements are examined so brand owners can generate compelling evidence of counterfeiting for legal proceedings. However, the ability to trace a product back to its origin is not supported unless a unique hidden tracing element is added to the product.

• Chemical and physical markers: These can be hidden from consumers and counterfeiters and can only be seen with specific detectors that are calibrated to a specific wavelength to verify authenticity.

• Tamper-evident packaging: These are labels, stickers or seals that, when opened or tampered with, provide immediate evidence that the product has been compromised.

• Serialisation: In the serialisation process, a company applies individual unique codes and/or signatures at the point of manufacture (giving each product an identifiable attribute) and defines scanning locations where retrieval and association of the unit can be linked to the scanning transaction. These transactions uniquely capture, track and store data from those markings in a managed database that allows authorised personnel to monitor the product journey by unit or larger groups. Most are familiar with this process as it applies to shipping a package overnight, where it is tracked online until it reaches its destination.

• Digital QR codes: Products can be scanned and authenticated without the need for an app, using a smartphone camera that can then further engage consumers by directing them to other web pages where they can register their warranty, learn more about the product, and even suggest other complementary products. As the product travels through the supply chain, the unique number or symbol can be collected in the database and added to its history. This information is available to a credentialed user via a mobile app or localised database. In a track and trace system, for instance, the information flow can be bi-directional, so the collection of the symbol, the scanning event and the unique call to the database can be recorded and appended to the product record for verification purposes.

• Online brand protection: The rise in online sales has unfortunately been accompanied by a rise in counterfeiting on online marketplaces, social media platforms and websites. Online brand protection tools include keyword monitoring, logo detection, image matching and the use of advanced brand protection technology like artificial intelligence and machine learning. Online brand protection allows your company to easily scan web pages and marketplaces, social media platforms, e-commerce apps, messaging apps like WeChat, payment sites and the dark web for infringing content and listings and get them taken down.

Case study 1: Pharmaceuticals

The challenge

Counterfeit copies of a major pharmaceutical brand were turning up in the US market, but the brand had no security measures in place to allow patients or inspectors to tell real products from fake. Consequently, $1 billion worth of product, already in the distribution pipeline, could not be sold until a method of allowing patients and retailers to verify that the medicine is authentic could be implemented.

The solution

The customer’s product was repackaged to include a variety of authentication features that could be identified by patients and inspectors, both in the field and in the laboratory. These included:

• overt, colour-shifting inks that were readily distinguishable by patients;

• covert, machine-readable inks that could be detected in the field by inspection staff with appropriate readers; and

• forensic markers that could only detected under laboratory analysis.

The outcome

The solution to the customer’s counterfeiting problem provided a secure way to instantly differentiate authentic from counterfeit medicines. The benefits were immediate and significant:

• $1 billion worth of product frozen within the supply chain was released for sale;

• the expense of a full product recall was averted;

• the customer was able to mitigate the risk of potential lawsuits; and, most importantly,

• confidence in the brand was restored among physicians, pharmacists and patients.

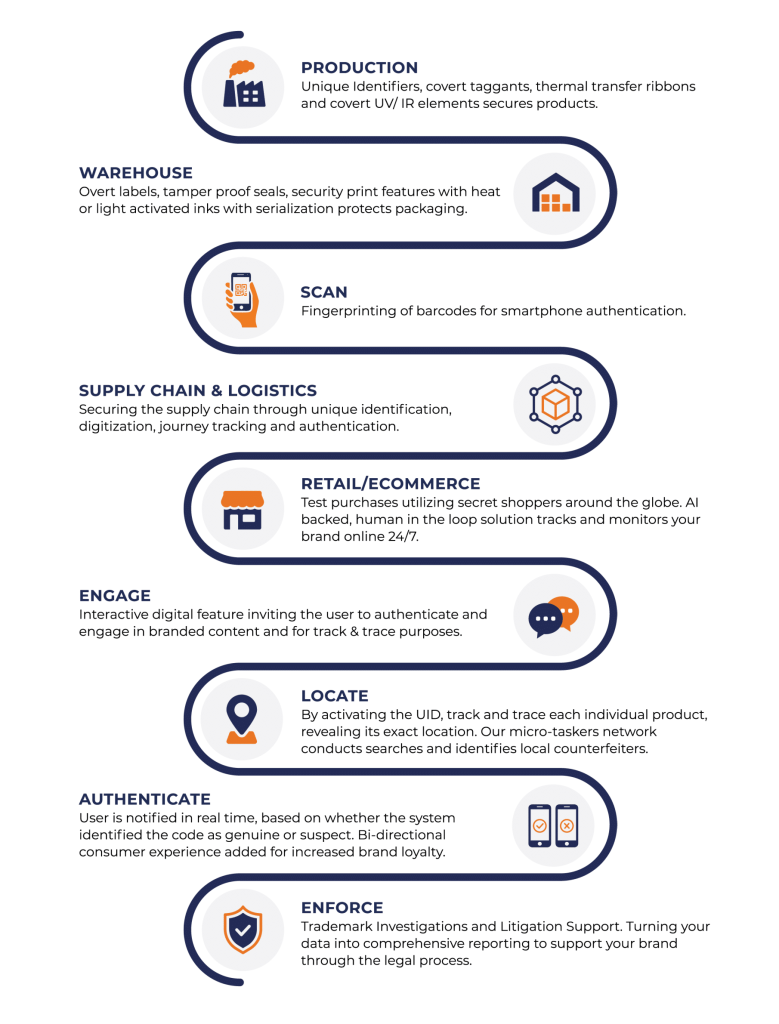

Implementing a multilayered approach: How brand protection works

The reality today is that one level of security is rarely sufficient. Counterfeiting technology is constantly evolving, so a simple one-dimensional technology to combat illicit trade isn’t enough. An effective multilayered approach in which overt, covert, and forensic features are applied is the most effective long-term solution.

These features can be incorporated into labels, closure seals, storage cartons, plastic, metal and glass packaging at very reasonable costs. Each type of feature serves a unique purpose, from colour-shifting inks that allow end-users to quickly identify a branded product as genuine to covert markings that enable an inspector to identify many factors involved with the source of authenticity.

Multilayered security options include:

• overt;

• covert;

• forensic;

• online monitoring;

• analysis – data collection and insight; and

• intellectual property and trademark enforcement.

Since any trademarked product can be counterfeited, it is imperative to have a brand protection strategy in place.

An effective brand protection programme spans many company departments, including marketing, legal, production, design, supply chain and logistics. That is a lot of moving parts to manage internally while companies are already busy making and selling the best products possible. The time these departments can dedicate to brand protection can be severely limited.

Having an external brand protection partner allows companies to have an entire team of experts in their corner, providing custom brand protection solutions built for each company’s unique situation using the most advanced technology paired with expert analysis.

A brand protection partner will also be able to share valuable insights and analytics to make further recommendations for what next steps the company can take to combat counterfeits. Brand protection partners can work with external teams, including law enforcement, border authorities, and investigators, to tackle counterfeit products at the source.

Case study 2: Wine and spirits

The challenge

A spirits brand based in South America needed help addressing counterfeiting and adulteration. It was losing millions in sales and experiencing a 30–40 per cent counterfeit rate, which put public safety and brand reputation at risk. An authentication solution was needed to make it easier for law enforcement and health agencies to distinguish authentic from counterfeit products in the field.

The solution

Multilayered security options were implemented throughout the programme, including a combination of in-product, on-package marking, and distribution channel monitoring. For on-package authentication purposes, an overt feature was added as tamper evidence for consumers and a covert feature was added for official retail inspectors to detect via handheld field verification readers and test kits. In addition, covert features were incorporated into the spirit itself for field and forensic lab verification.

The outcome

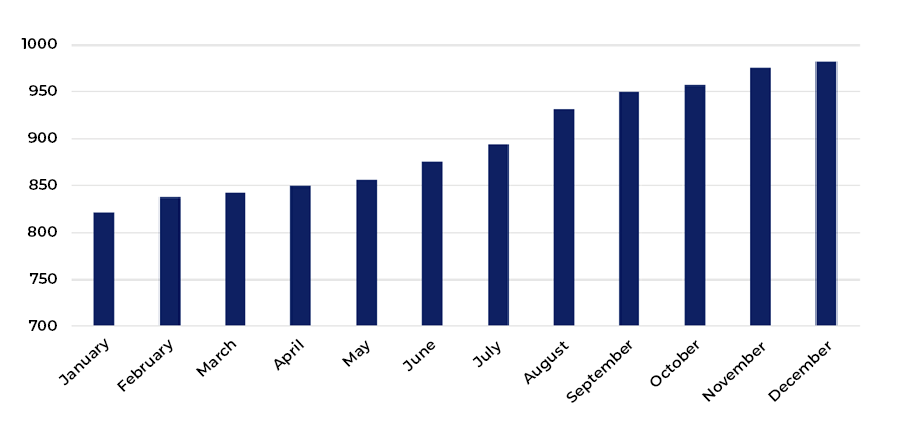

• Within the first year of the programme, 75 million litres of spirits were protected (approximately 100 million bottles).

• More than 1,300 inspectors in 28 states inspected more than 300 retail outlets.

• Of these, 10 per cent were found to contain counterfeits; five retail outlets were investigated, resulting in arrests.

• The brand owner experienced a 25 per cent increase in sales over the same period.

Conclusion

Employing an effective brand protection solution brings a wide range of benefits to businesses. Improving sales and revenue is always important in any industry. By eliminating infringements and counterfeits, a company can increase revenue and market share.

Having a brand protection partner that manages detecting, monitoring and taking down counterfeiters allows businesses to save valuable time and focus on producing and selling instead of worrying about bad actors. Customers will also notice a rise in brand standards once the lower-quality infringing products are removed from the market. This generates goodwill and improves brand reputation.

Eliminating low-quality, counterfeit products not only saves businesses from financial drain but also solidifies their reputation among consumers and partners alike. This newfound trust translates into lasting customer loyalty and gives businesses a competitive edge. Additionally, brand protection strategies reduce legal risks and provide actionable insights by having greater supply chain visibility and data, setting the company up for even greater success.

For a more complete guide to brand protection- why it is necessary, how infringement harms brands and customers, how to develop and implement an effective program, and insights into the brand protection strategies of the future – download our Complete Brand Protection Guide.

Download the Guide

About Authentix

As the authority in authentication solutions, Authentix can help brands create a customized plan to tackle counterfeit products from every angle, collect actionable data, and protect brands and consumers. Authentix works with each company to determine which brand protection solutions are right for their situation.

Authentix brings enhanced visibility and traceability to today’s complex global supply chains. For over 25 years, Authentix has provided clients with physical and software-enabled solutions to detect, mitigate, and prevent counterfeiting and other illicit trading activity for currency, excise taxable goods, and branded consumer products. Through a proven partnership model and sector expertise, clients experience custom solution design, rapid implementation, consumer engagement, and complete program management to ensure product safety, revenue protection, and consumer trust for the best known global brands on the market. Headquartered in Addison, Texas USA, Authentix, Inc. has offices in North America, Europe, Middle East, Asia, and Africa serving clients worldwide.